Sikkim’s journey from a secluded Himalayan kingdom to the 22nd state of the Indian Union is a saga woven from centuries of monarchy, colonial maneuverings, urgent strategic calculations, ethnic complexity, and the eventual triumph of democratic aspirations. Marking 50 years since Sikkim’s formal statehood in 1975, this article explores Sikkim’s pre-integration status, the pivotal figures and events behind its merger with India, and the subsequent evolution of its politics and society. It thoroughly investigates the treaties, power struggles, constitutional amendments, and the ethnic and strategic considerations that shaped Sikkim’s political trajectory. By piecing together a wealth of scholarly, governmental, and media sources, this article provides a full and nuanced account for both academic and general audiences.

Monarchical Foundations: The Namgyal Dynasty and Sikkim’s Early History

From its founding in 1642 by Phuntsog Namgyal, crowned as the first Chogyal (Dharma King) by three revered lamas, Sikkim became a theocratic monarchy deeply rooted in Tibetan Buddhism and Himalayan traditions. This Namgyal dynasty endured for over three centuries, weathering repeated external invasions from Bhutan, Nepal, and Tibet, and internal succession disputes. The Chogyals were considered both temporal and spiritual leaders—a status echoed in the infrastructural and ritual centrality of monasteries (Lamaseries) throughout Sikkim. Over time, the kingdom’s political and social fabric became intricately interlaced with the destinies of the Lepchas (indigenous to Sikkim), Bhutias (of Tibetan origin), and Nepalis (who migrated in large numbers during the 19th and early 20th centuries).

The monarchy’s legitimacy was reinforced by an origin myth—Guru Rinpoche, the patron saint of Sikkim, was said to have prophesied the Chogyal’s rule. The crowning of Phuntsog Namgyal was performed by three lamas arriving from the north, west, and south, an act embedding the monarchy within a tapestry of regional Buddhist religious authority. The Chogyals ruled from various capitals—Yuksom, then Rabdentse, Tumlong, and finally Gangtok—adapting to the practicalities of defense and governance. Yet, as Sikkim’s external threats shifted, so too did its geopolitical posture and dependence on foreign powers.

Sikkim’s Strategic Position and the Onset of British Influence

From the late 18th to the 20th centuries, Sikkim’s fate was buffeted by the expansionist pressures of neighboring powers. Frequent Gorkha incursions from Nepal and territorial losses to Bhutan pushed Sikkim’s rulers to seek an alliance with the British, who were themselves looking to counter Nepalese influence and secure a trade route to Tibet. This mutual interest crystallized in landmark treaties:

Treaty of Titalya (1817)

The Treaty of Titalya, inked in 1817 between the Sikkimese Chogyal and the British East India Company, followed the conclusion of the Anglo-Nepalese War. Its main achievement was to restore territories west of Teesta—previously seized by Nepal—to Sikkim. In return, the British acquired trading rights and secured their position as arbiters in Sikkim’s disputes with neighbors, a role codified in subsequent documents as Sikkim’s “paramountcy” under British protection.

Treaty of Tumlong (1861)

The Treaty of Tumlong signified an even greater shift, making Sikkim a “de facto British protectorate.” The then Chogyal, Sidkeong Namgyal, signed away significant autonomy: British authorities secured rights to build infrastructure, intervene in Sikkim’s internal affairs, and mandate customs and road construction, as well as station a political officer in Gangtok. Free trade for British subjects and indemnities became the economic corollaries of this new relationship.

Calcutta Convention (1890) and Lhasa Convention (1904)

The Convention of Calcutta (1890) was a bilateral Anglo-Chinese agreement recognizing British protectorate status over Sikkim and demarcating its border with Tibet. However, Tibet’s refusal to acknowledge this arrangement—against the backdrop of the “Great Game” and imperial rivalries—set the stage for the forceful 1904 British expedition to Lhasa and the subsequent Convention of Lhasa, consolidating British-run trade and travel through the region.

The cumulative effect of these treaties transformed Sikkim from a relatively independent Himalayan kingdom to what scholars describe as a “colonial periphery state”—not directly annexed but subject to external control over its foreign relations, defense, and crucial economic levers.

Sikkim’s Ambiguous International and Legal Status Post-1947

As the British Raj faded in 1947, the legal position of Sikkim was ambiguous. Unlike most princely states, Sikkim was not a full sovereign state nor a “Native State”; its protectorate status was sui generis and left deliberately undefined in British policy documents and legal instruments. The Government of India claimed to inherit all “paramount” rights, but the Sikkimese court argued otherwise, insisting that sovereignty reverted to the Chogyal and his council.

Standstill Agreement, 1947

To prevent any administrative vacuum during the transition to independence, India signed a “standstill agreement” with Sikkim, Nepal, Bhutan, and Tibet. This arrangement preserved all pre-existing relations, agreements, and controls until renegotiated.

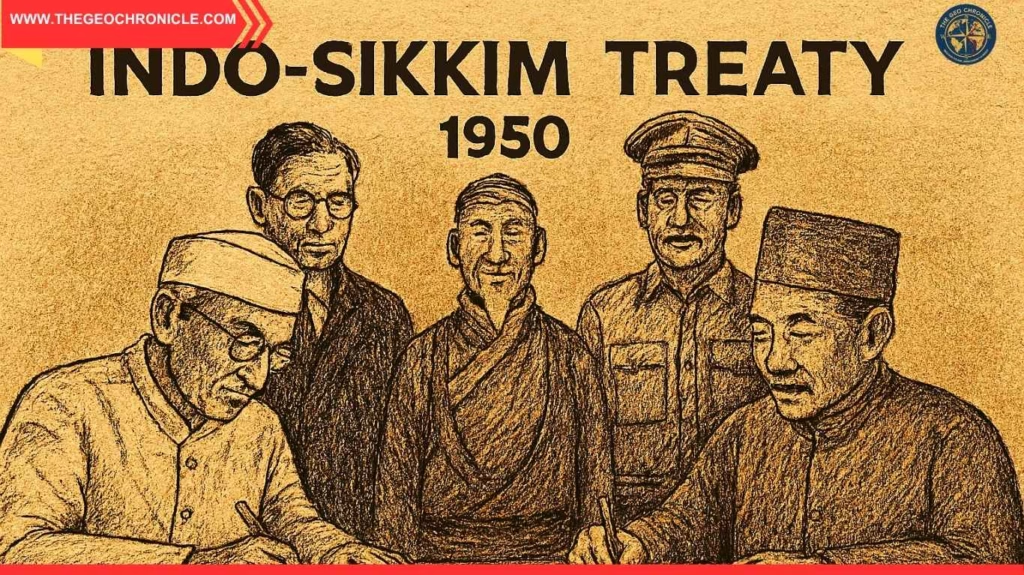

Indo-Sikkim Treaty, 1950

By 1950, after the eruption of anti-feudal protests and a short-lived administrative breakdown, Sikkim entered into the Indo-Sikkim Treaty. The Chogyal was recognized as internal sovereign, but India assumed comprehensive responsibility for defense, foreign policy, and communications. Indian nationals and Sikkimese were given reciprocal rights to engage in trade and movement, while Indian law applied to Indian nationals in Sikkim. A permanent Indian “representative” was stationed in Gangtok, with powers extending to the extradition of fugitives and the construction of strategic infrastructure.

Although Sikkim retained its monarchy, internal autonomy, and separate legal system, its fate was increasingly tied to Indian strategic interests, especially as tensions on the India-China border became acute after 1962.

Evolving Political Movements and the Crisis of Monarchical Authority

Demographic and Political Complexities

Sikkim’s demography had changed radically since the mid–19th century, owing to British-encouraged Nepali settlement. By the early 20th century, Nepalis formed a majority, with Lepchas and Bhutias constituting around a quarter of the population combined. However, the political order remained anchored to the Bhutia-Lepcha elite and Buddhist institutions. This imbalance, reinforced through tailored voting rights, landholding laws, and religious authority, sowed seeds of resentment among the excluded majority and non-elite minorities.

Early Democratic Agitations

The modern era of political contestation in Sikkim began in the mid-20th century. The late 1940s and 1950s witnessed a series of protests against the feudal order and demands for democratic representation, spearheaded by organizations such as the Praja Sudharak Samaj, Praja Mandal, and Sikkim State Congress. Their leading figures—Tashi Tshering, Kazi Lhendup Dorjee, and others—demanded an end to landlordism, the parity voting system, and the establishment of responsible government.

Notable Pre-Merger Political Parties

| Party Name | Community Base | Ideology & Core Demand | Notable Leaders |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sikkim State Congress | Nepalese | Democracy, “One man one vote”, Abolition of monarchy, Merger with India | Tashi Tshering, later Kazi Lhendup Dorjee |

| Sikkim National Party | Bhutia-Lepcha | Preserve monarchy, Sikkimese autonomy, Status quo | Palace-backed |

| Sikkim National Congress | All ethnicities | Cross-communal democracy, Responsible government, Closer association with India | Kazi Lhendup Dorjee |

| Sikkim Janata Congress | Merged with SNC | Democratic reforms |

Modern political history in Sikkim was thus characterized by a standoff between “integrationist” and “status quoist” forces, with India serving at once as a guarantor and potential disruptor of the delicate ethnic balance.

The Road to Integration: Key Events and Actors

The 1960s–Early 1970s: Mounting Tensions

The death of Chogyal Tashi Namgyal in 1963 brought Palden Thondup Namgyal to the throne amid growing Indian strategic anxiety after China’s assertion in Tibet. Chogyal Palden, attempting to assert greater independence in foreign affairs and offset the Nepali majority, moved closer to China diplomatically, alarmed Indian officials, and further alienated key sections of the populace.

Meanwhile, the Sikkim Subject Regulation of 1961, which defined categories of citizenship and land rights, further stoked ethnic divisions. “Natural subjects,” mainly Bhutia-Lepchas, were distinguished from “domiciled subjects” (Nepali settlers before 1946), with further layers excluding Indian traders. Land reforms and the link between property rights and citizenship created inequalities that would persist even after integration.

The 1973 Political Crisis and Tripartite Agreement

Widespread discontent flared into open agitation after the 1973 State Council elections, which opposition parties alleged were rigged by the palace-backed National Party. The aggrieved Sikkim National Congress, led by Kazi Lhendup Dorjee, along with other opposition groups, launched mass protests demanding “one man, one vote,” real democracy, and a reduction of monarchical power. The resulting unrest paralyzed Gangtok, and the Chogyal, faced with popular anger and administrative collapse, requested Indian intervention.

Indian authorities deployed officials—including figures such as Ajit Doval (then with the Intelligence Bureau)—to administer Sikkim and broker negotiations. The 8 May 1973 Tripartite Agreement, signed between the Chogyal, the Government of India, and key political parties, established a new constitutional regime:

- Guaranteed human rights and fundamental freedoms

- Assembly with elected representatives under universal adult suffrage

- Chief Executive—a nominee of the Government of India

- Retention of the Chogyal as a titular head, but real executive power with the council and Chief Executive

- Provisions for reservations to ensure ethnic balance (parity between Bhutia-Lepcha and Nepalis), as seen in the composition of the Assembly and Cabinet

Indian control over Sikkim’s external affairs, defense, and administration was now virtually total, though not yet formalized as an outright merger.

The Final Years of the Monarchy: Elections, Constitution, and Referendum

The 1974 Elections and New Constitution

The first universal adult franchise elections held in April 1974, conducted under the supervision of the Election Commission of India, marked a turning point. The Sikkim National Congress, now merged with various democratic and pro-integration factions, swept the polls, capturing 31 of 32 Assembly seats. The Chogyal’s supporters were nearly eliminated from the political scene.

The Assembly, reflecting the aspirations voiced in the 1973 agreement, passed the Government of Sikkim Bill, which was promulgated as the new constitution. This statute:

- Curtailed the monarch’s powers to a titular head

- Provided for Chief Minister and Council of Ministers, with the Chief Executive holding ultimate authority, subject to India’s approval

- Opened the door (in Section 30(c)) to “participation and representation for the people of Sikkim in the political institutions of India” — a move widely seen as signaling impending merger

Towards Statehood: Associate Statehood and the 1975 Referendum

In September 1974, Parliament adopted the 35th Constitutional Amendment, creating the unique category of “associate state” for Sikkim under Article 2A, backed by the Tenth Schedule which defined its association with India and ensured representation in the Parliament, but withheld full statehood.

However, the Chogyal publicly protested the dilution of Sikkim’s autonomy and attempted to internationalize the dispute. The political climate deteriorated sharply; reports of palace intrigue, ethnic mobilization, and even the Chogyal’s supposed moves to solicit Chinese support prompted a unanimous resolution in the Sikkim Assembly—backed by popular demonstrations and Kazi Lhendup Dorjee’s government—calling for the abolition of the monarchy and outright integration into India.

A special referendum, held on 14 April 1975, saw nearly 98% of voters (59,637 out of 61,133 participants) endorsing the abrogation of the monarchy and unconditional union with India. Although the legitimacy of the referendum was later questioned by some critics, its political and symbolic importance was undeniable.

Key Events in the Integration of Sikkim

| Year | Event |

|---|---|

| 1642 | Phuntsog Namgyal crowned first Chogyal—foundation of the Namgyal dynasty |

| 1817 | Treaty of Titalya—British become paramount power in Sikkim |

| 1861 | Treaty of Tumlong—Sikkim becomes British protectorate |

| 1890, 1904 | Calcutta Convention and Lhasa Convention—border definitions and consolidation of British influence |

| 1947 | Indian independence, Standstill Agreement with Sikkim |

| 1950 | Indo-Sikkim Treaty—protectorate status under Indian suzerainty |

| 1973 | Mass anti-monarchy demonstrations; Tripartite Agreement signed (8 May) |

| 1974 | Adult franchise elections, New constitution, 35th Amendment: “associate state” status |

| 1975 | Referendum abolishing monarchy; 36th Amendment (full statehood); Sikkim becomes 22nd state of India (16 May) |

The 35th and 36th Constitutional Amendments & Article 371F

The Thirty-Fifth Amendment (1974): Associate Statehood

The 35th Amendment created for Sikkim a unique constitutional experiment—an “Associate State” category. This status recognized Sikkim’s close association without full statehood. It:

- Introduced Article 2A and the Tenth Schedule, stipulating India’s full control of Sikkim’s defense, external affairs, and essential administration

- Provided Sikkim with representation in the Rajya Sabha and Lok Sabha

- Established that Parliament could legislate for Sikkim and oversee its elections

The Thirty-Sixth Amendment (1975): Full Statehood

Following the referendum, Parliament moved swiftly. The 36th Amendment:

- Added Sikkim as Entry 22 in the First Schedule (i.e., among Indian states)

- Inserted Article 371F, a comprehensive framework to manage Sikkim’s unique context

Article 371F: Special Provisions

Article 371F is the cornerstone of Sikkim’s integration, designed to balance the need for integration with the preservation of local identity and rights.

Key features include:

- Guaranteeing a minimum of 30 MLAs in the state Assembly

- Mandating that the sitting Assembly (elected in 1974) be treated as the state’s Legislative Assembly

- Allowing for legislative protection of minority rights and ethnic diversity (Parliament can reserve Assembly seats for different sections)

- Special powers for the Governor in matters of peace, social justice, and communal balance

- Continued validity of all pre-existing Sikkimese laws, unless amended or repealed by Parliament

- Exemption of older disputes and treaties from the jurisdiction of Indian courts (clause (m))

- The President of India may, by order, extend any Indian law to Sikkim (with modifications), within two years of merger

- Land and employment rights reserved for Sikkimese registered as of 1961; old Sikkimese (“Sikkim Subjects”) enjoy significant legal benefits

Sikkim’s special constitutional provisions continue to be a subject of debate about autonomy, ethnic rights, and integration in contemporary India.

Immediate Political Changes After Merger: Governance and Electoral Politics

Administrative Restructuring

With merger, the transfer of Sikkim’s administration from the Ministry of External Affairs to the Ministry of Home Affairs occasioned both symbolic and practical changes, reorganizing Sikkimese governance along Indian administrative, fiscal, and political frameworks. New institutions and procedures unfamiliar to Sikkim’s populace and elite were introduced—provoking both optimism among marginalized communities and skepticism among the old elite.

Post-Merger Electoral Developments

The years after merger saw a rapid transformation in Sikkim’s party politics and ethnic alignments:

The 1979 and Subsequent Elections

- The Sikkim Pradesh Congress (formerly Sikkim Congress)—initially the dominant pro-merger party under Kazi Lhendup Dorjee—was eventually sidelined due to internal conflict and rising dissidence.

- The reservation system for Bhutia-Lepchas remained but was adjusted, reducing seats and broadening to include other tribals. No similar reservation was offered to the Nepalis, despite their majority status, leading to persistent unrest.

- In the 1979 elections, the Sikkim Janata Parishad (SJP), an anti-merger, pro-autonomy party, emerged victorious, capitalizing on the government’s perceived failings and the “Black Bill” (Bill 79) controversy over representation, citizenship, and land reform.

- From the 1980s through the 2000s, electoral outcomes and party realignments largely reflected enduring ethnic and policy tensions—often with high turnover in ruling parties but little sustained challenge to the fact of merger.

- The reservation of seats for the Buddhist Sangha (monasteries), unique in India, was maintained in the Assembly, a controversial but telling measure of Sikkim’s distinctiveness.

Contemporary Electoral Politics

Today, Sikkim’s politics remain dynamic. Generations of political leaders—Nar Bahadur Bhandari (SJP/SSP), Pawan Kumar Chamling (SDF), and Prem Singh Tamang (SKM)—have rotated power, each seeking to balance local autonomy, development, and integration with India. The 2024 elections saw the Sikkim Krantikari Morcha win a landslide, reaffirming a trend of competitive but largely stable electoral democracy.

Ethnic Politics, Reservation, Land, and Citizenship Issues

Ethnic Reservations and Political Representation

Despite being numerically inferior, Bhutia-Lepchas have historically enjoyed constitutional protection regarding land, jobs, and political reservations—a system designed to safeguard minority interests in a majoritarian milieu. These arrangements, however, have often been contested by Sikkimese Nepalis, who view their lack of reserved legislative seats as an affront to democratic equality.

The issue of the reserved Sangha seat is similarly contentious, with critics arguing that religious seats violate the secular character of Indian democracy, while defenders contend that the Buddhist clergy have always played a vital role in Sikkimese society and politics.

Land and Legal Rights

The 1961 Sikkim Subject Regulation—retained in certain forms under Article 371F—established a complex hierarchy of rights concerning land ownership, citizenship, and even marital status for Sikkimese women marrying non-citizens. The protection of land for Bhutia-Lepcha “natural subjects” persisted through post-integration reforms, often transposing old landed elite privileges into the new system.

With the inclusion of Sikkim into the Indian Union, those who were Sikkim Subjects by 26 April 1975 became Indian citizens, but property rights, government job eligibility, and affirmative action continue to be entangled with registration under older Sikkimese laws. A 2023 expansion of the “Sikkimese” definition for income tax exemption purposes has stirred concerns about dilution of indigenous privileges.

Socio-Economic Transformations and Development after Integration

Economic Growth and Structural Change

The integration with India marked a dramatic economic transformation:

- Funds and Investment: Central government aid became the main engine powering Sikkim’s economic and social progress. Over 60% of Sikkim’s revenue now comes from central grants, and a “dependency economy” has emerged, risking fiscal unsustainability if central support wanes.

- Industrialization: Sikkim has rapidly industrialized, especially in pharmaceuticals and hydropower, with manufacturing now comprising nearly half the state’s GSDP as of 2025.

- Poverty Reduction: Poverty has plummeted from over 50% in the early 1970s to less than 3% in 2025, while health and education indicators have noticeably improved.

Land and Agriculture

Sikkim is the first Indian state to convert entirely to organic farming—a major policy and branding initiative supported by both local and central government. Cardamom, ginger, and tea are particularly prominent exports. Infrastructure, especially roads and the relatively new Pakyong airport, has slowly mitigated Sikkim’s remoteness, facilitating commerce and tourism.

Tourism and Ecology

Tourism flourishes with “zero waste” and “organic” branding, leveraging the state’s rich biodiversity hotspots (Mount Kanchenjunga, lakes, monasteries) and unique Buddhist culture. However, the relentless focus on tourism and hydropower poses sustainability challenges amidst fragile Himalayan landscapes.

Strategic and Geopolitical Implications of Sikkim’s Integration

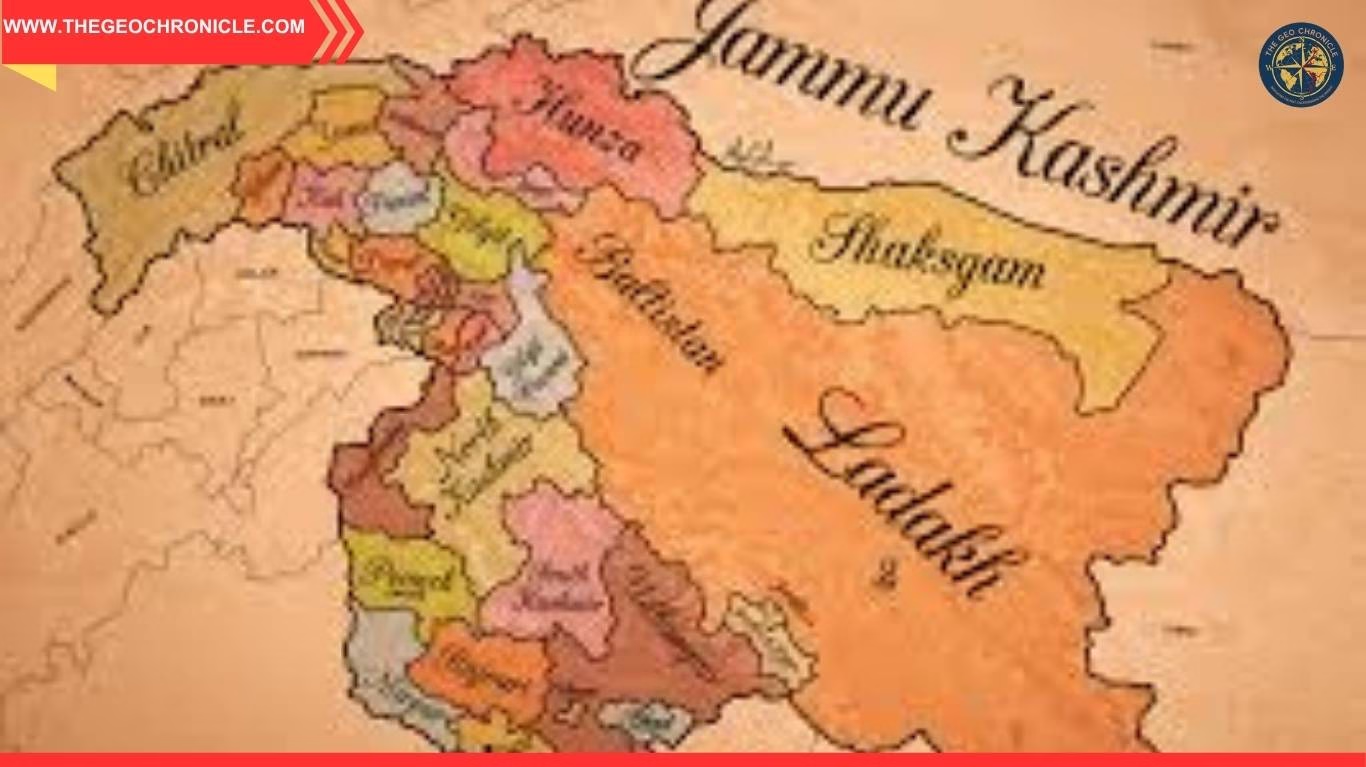

Sikkim remains a linchpin in the broader Himalayan security scenario:

- Geostrategic Position: Bordered by China (Tibet), Bhutan, and Nepal, Sikkim commands vital mountain passes (Nathu La, Jelep La), which were flashpoints in historic face-offs with China, including the 1967 clashes and the more recent Doklam standoff in 2017.

- Buffer against China: The blurring of the Sikkim–Tibet (China) border could have afforded Beijing an easier approach to India’s strategic Siliguri Corridor (“Chicken’s Neck”), amplifying Sikkim’s centrality in India’s defensive calculations.

- International Recognition: China did not recognize India’s sovereignty over Sikkim until 2003, and Sikkim’s status has occasionally figured in border dispute rhetoric.

- Cross-Border Trade: The reopening of Nathu La in 2006 under India-China confidence-building was intended to revive old trade networks, though volumes and routes are still hampered by border tensions, seasonal access, and bureaucratic restrictions.

Contemporary Political and Constitutional Issues

Ongoing Debates

The legacy of special status under Article 371F remains contentious. While it preserves Sikkimese identity, law, and land traditions, it is also cited as a source of friction over reservation, job quotas, native status, and inheritance laws. The inclusion of additional groups within the ambit of “Sikkimese” for tax purposes in the 2023 Finance Bill has generated fears of the erosion of indigenous rights.

Legal and constitutional challenges persist—especially relating to the reservation of religious (Sangha) seats in the Assembly, the scope of protection for “old Sikkimese,” and the sporadic assertion of pro-autonomy sentiment by some sections. Yet, there is widespread acceptance that merger with India is irreversible, even as debates persist over the precise contours of integration, autonomy, and justice.

Conclusion: Lessons of Integration and the Path Ahead

The integration of Sikkim into India is a striking illustration of how historical accident, demographic change, colonial legacies, regional geopolitics, and the winds of democratic change interact in contemporary South Asia. Sikkim’s statehood brought profound challenges and opportunities—dismantling a monarchy, transforming social relations, fostering rapid economic growth, and recasting the kingdom’s international status.

Yet, the story is far from static. As Sikkim marks 50 years as a state, it continues to grapple with balancing development with ecological sustainability, accommodating ethnic complexity with justice, and securing its place in a changing geopolitical map. The lessons of Sikkim—about negotiated integration, the limits of political engineering, and the resilience of local identity—remain deeply relevant for India, its neighbors, and comparative political studies worldwide.

Disclaimer

This article is based on publicly available sources and official documents as of October 2025. While every effort has been made to ensure accuracy and comprehensive coverage, interpretations and perspectives may evolve as new scholarship and government policies emerge. The content is intended for informational and educational purposes. Readers are encouraged to verify facts and interpretations using the cited primary and secondary sources.

Leave a Reply