On the morning of May 18, 1974, a seismic event shook the sands of Rajasthan’s Pokhran Test Range—an event that reverberated far beyond India’s arid western desert and transformed the architecture of global nuclear politics. Code-named “Smiling Buddha,” India’s first underground nuclear bomb test was the country’s first explicit demonstration of nuclear weapons capability, making India the sixth nation—outside the five permanent UN Security Council members—to master atomic explosives. Framed publicly by Indian officials as a “peaceful nuclear explosion,” the test marked a dramatic pivot in India’s strategic posture, sparked sweeping international reactions, and permanently altered the contours of nuclear non-proliferation regimes.

Origins of India’s Nuclear Programme (1944–1954)

The framework of India’s nuclear journey predates independence, rooted in efforts by the brilliant physicist Dr. Homi Jehangir Bhabha. Recognizing the transformative potential of atomic science, Bhabha proposed the creation of a research institute in March 1944, which led to the founding of the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research (TIFR) in December 1945 in Mumbai, powered by a grant from the Sir Dorabji Tata Trust. The objective was to nurture scientific talent and build a bedrock for advanced physics research, particularly in nuclear and cosmic ray studies.

The end of World War II—after Hiroshima and Nagasaki—had thrust nuclear issues to the forefront of global security debates. For Jawaharlal Nehru, India’s first prime minister, nuclear technology represented both a beacon for social progress and an existential threat. As early as 1948, the Atomic Energy Act was passed, establishing the Indian Atomic Energy Commission (IAEC), with Bhabha as its first chairman. Nehru declared, “We are interested in atomic energy for social purposes. It will be a tremendous boon to mankind”.

India’s pursuit of atomic energy was intertwined with broader post-colonial aspirations of self-reliance, scientific modernization, and national strength. Bhabha’s vision extended beyond civilian energy: he anticipated, even in the mid-1940s, that “nuclear energy… will not have to look abroad for its experts but will find them ready at hand”.

Establishment of Research Infrastructure (1954–1961)

India’s nuclear momentum intensified during the 1950s. The Department of Atomic Energy (DAE) was created in 1954, with Bhabha at the helm as Secretary and with direct reporting to the Prime Minister—an arrangement that reflected the strategic priority attached to the nuclear program.

In January 1954, the Atomic Energy Establishment, Trombay (AEET), was set up as a dedicated campus for nuclear research and technology—later renamed the Bhabha Atomic Research Centre (BARC) after Bhabha’s tragic death in 1966. BARC would become the nucleus of all Indian bomb-related research activity.

Two milestones defined early research infrastructure:

- APSARA Reactor: In August 1956, India commissioned Asia’s first operational research reactor, APSARA, built with British assistance. This pool-type reactor enabled experiments in reactor physics and plutonium production.

- CIRUS Reactor: The game-changing moment was Canada’s agreement (1955) to supply a 40 MW heavy-water moderated reactor, CIRUS (Canada-India Reactor Utility Services), operational by July 1960. CIRUS was ideally suited for producing weapons-grade plutonium, and India, to maintain autonomy, manufactured its own natural uranium fuel, side-stepping potential foreign constraints.

BARC scientists were soon working on uranium and thorium fuel cycles, reprocessing technology, and heavy water production—a foundation that made the later weaponization process domestically sustainable.

Political Leadership and Policy Shifts (1947–1965)

India’s nuclear outlook was initially shaped by Nehru’s dual commitment to science-led progress and disarmament. Though Nehru remained personally averse to nuclear weapons, he insisted that India should develop expertise to avoid reliance on foreign powers. Bhabha—while echoing these sentiments in public—quietly built up the latent capacity for weapons, under the logic that the “technology for the construction of any nuclear explosive device is indistinguishable from the technology involved in a nuclear explosive weapon”.

This tightrope walk persisted until the 1962 Sino-Indian War, a turning point that exposed India’s conventional vulnerabilities vis-à-vis China. Nehru and his successors (Lal Bahadur Shastri, Indira Gandhi) sought security guarantees from established nuclear powers, but aid was not forthcoming. Under domestic pressures and growing regional insecurity, India remained steadfastly outside the emerging Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT), which “created an arbitrary division between nuclear haves and have-nots”—a formulation Indian policymakers would consistently denounce as discriminatory.

After Nehru’s death in 1964 (and Bhabha’s in 1966), the program’s direction shifted. Under Vikram Sarabhai, there was a renewed emphasis on “peaceful” nuclear energy, but regional and global developments would soon catalyze a return to more ambitious objectives.

The 1962 Sino-Indian War and Changes in Nuclear Strategy

In October 1962, a humiliating defeat at the hands of China, coupled with Beijing’s first successful atomic bomb test at Lop Nur in 1964, shocked Indian leaders into reconsidering the necessity of a nuclear deterrent. The war heightened perceptions of China as a “logical threat” and contributed to the formal demand for weaponization within India’s Parliament.

Intense internal debates ensued. Still, it was increasingly understood that civilian mastery of the nuclear fuel cycle could be rapidly converted to military purposes if needed. Preliminary studies into weapon physics began at TIFR and AEET/ BARC, focusing on reactor-grade plutonium and the theoretical design of implosion weapons.

Bhabha and his successors framed nuclear weapon work as investigations into “peaceful nuclear explosives” (PNEs)—a notional cover for weapons research, but one that allowed India to develop critical technical expertise while minimizing international scrutiny. This ambiguous stance would persist through the first test in 1974.

CIRUS Reactor and Plutonium Production

The CIRUS reactor at BARC became central to India’s weapons program. Modeled after Canada’s Chalk River NRX reactor, CIRUS used heavy water supplied by the U.S. and provided an annual production capacity of about 6-10 kg of weapons-grade plutonium, enough for one or two bombs each year.

In 1957, groundwork began for a plutonium reprocessing facility using the PUREX process—this “Project Phoenix” plant in Trombay came online in 1964. By then, India had two major reactors (APSARA and CIRUS), experience in handling nuclear materials, and the capacity to produce bomb-ready plutonium—a combination that gave it the option of “latent” weaponization at any moment.

Barred from exporting technology under the Atoms for Peace program, India insisted that all technology and materials supplied to it could be used for “any peaceful purposes,” a formulation Canada and the U.S. initially accepted but later contested after 1974.

Design and Development of the Smiling Buddha Device

Project Genesis and Leadership

With the return of Indira Gandhi as Prime Minister in 1966, program momentum returned. During a September 1972 visit to BARC, Gandhi verbally authorized the project’s leaders—including Dr. Raja Ramanna (BARC Director), P.K. Iyengar (BARC Deputy Director), and others—to prepare a device for testing. Gandhi’s circle of trust was small: only a handful of advisers and no other government ministers were fully briefed, a deliberate act to maximize operational secrecy.

Raja Ramanna was the operational mastermind, coordinating with senior scientists such as Rajagopala Chidambaram, P.K. Iyengar, and B.D. Nag Chaudhuri (DRDO). Seventy-five select scientists and engineers were involved, each sworn to utmost secrecy.

Technical Innovation

The Indian device used implosion-type technology with a plutonium core, similar to the U.S. Fat Man bomb. Fabricating the plutonium core—roughly 6 kg from CIRUS—was among the most challenging tasks, requiring advanced metallurgy and criticality safety expertise. The neutron initiator, code-named “Flower,” was a polonium–beryllium device designed to launch the chain reaction at the moment of maximum compression.

The high-explosive lenses, implosion system, and detonators were developed by DRDO’s Terminal Ballistics Research Laboratory and Explosive Research and Development Laboratory, leveraging home-grown talent and a decade of experience in explosives research. The device was hexagonal, about 1.25 meters in diameter, weighing 1,400 kg.

Execution and Secrecy

Preparations at Pokhran were camouflaged as routine army engineering work. Indian Army engineers dug the shaft—over 100 meters deep—in what was code-named Operation Dry Enterprise. Test components were transported under cover of darkness, and assembled at a hut 40 meters from the shaft. Final assembly was performed in arduous desert conditions, sometimes hindered by technical and logistical snags. The device was ultimately mounted on a tripod, transported into the L-shaped underground shaft, and sealed with sand and cement.

Even up to the day of the test, secrecy was so tight that Defense Minister Jagjivan Ram and other senior officials were only informed at the last minute—a testament to India’s internal security apparatus and organizational discipline.

The Pokhran Test: Day of Detonation and Technical Details

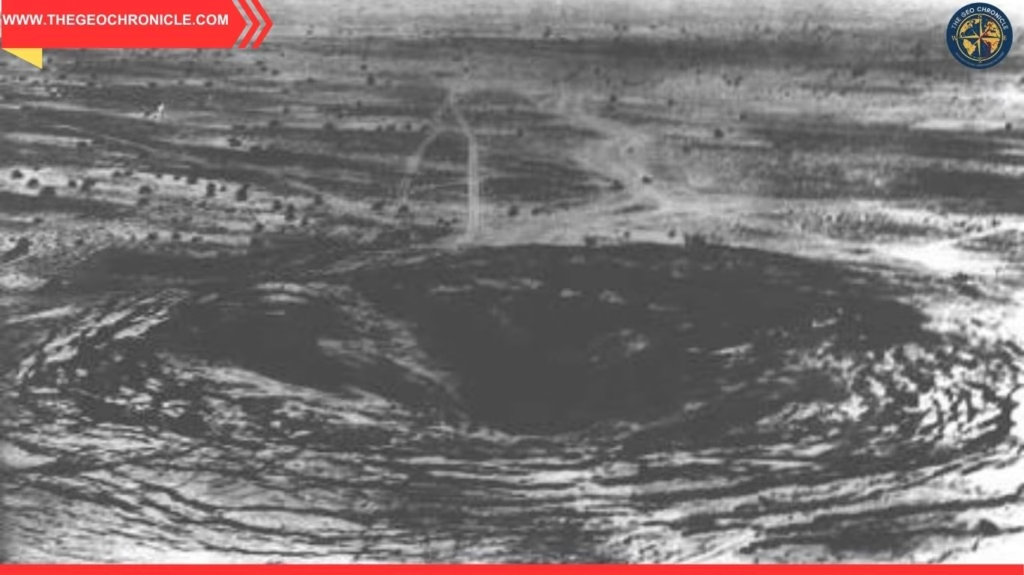

At 8:05 a.m. on May 18, 1974, scientist Pranab Rebatiranjan Dastidar pressed the firing button from an observation bunker 5 km away, after a five-minute delay caused by a stranded jeep and a last-minute check by TBRL engineer V.S. Sethi. The detonation produced a subsidence crater about 47 meters in radius and 10 meters deep in the Thar desert.

Yield Analysis

There has been ongoing debate about the device’s yield. While initial estimates from Indian officials suggested 10–12 kilotons, later analyses by independent experts (including seismic data) have estimated the actual yield at closer to 8 kilotons, matching one “Fat Man” bomb and validating the design claims of the technical team.

Device Highlights (Graphical Table)

| Component | Details |

|---|---|

| Core | ~6 kg plutonium from CIRUS reactor |

| Implosion System | 12 high-explosive lenses, DRDO designed |

| Neutron Initiator | Polonium–beryllium (“Flower”) |

| Assembly | 1.25 m hexagonal, 1,400 kg, tripod mounted |

| Detonation Depth | 107 meters underground (L-shaped shaft) |

| Yield | Officially 10–12 kt, independently ~8 kt |

| Date/Time | 18 May 1974, 8:05 AM IST |

| Secrecy | <100 people, tightest operational secrecy |

The elaborate preparation and meticulous attention to security meant the world remained unaware of the test until formal announcement, much to the chagrin of Western intelligence agencies.

Key Individuals: Scientific and Political Architects

Dr. Homi Jehangir Bhabha

Often called the “father of the Indian nuclear programme,” Bhabha’s multidisciplinary genius and institution-building vision laid the groundwork for every Indian nuclear success. Through TIFR, AEET/BARC, and the Atomic Energy Commission, Bhabha positioned India to maximize scientific self-reliance and manage the full nuclear fuel cycle domestically. His advocacy, both public and subtle, for latent nuclear option led to technical and human capital assets that successors could mobilize for strategic aims.

Dr. Raja Ramanna

A protégé of Bhabha, Ramanna assumed direct leadership after Bhabha’s death. Trained in physics and explosives, Ramanna orchestrated the bomb’s design, built and led the core team at BARC, and managed operational complexities at Pokhran. In later years, he candidly acknowledged: “The Pokhran test was a bomb… I just want to make clear that the test was not all that peaceful”—an admission that confirmed what the world had long suspected: Smiling Buddha was weapons development in everything but official name.

P.K. Iyengar, R. Chidambaram, and Others

Supporting pillars included P.K. Iyengar (deputy/project manager), R. Chidambaram (core physics and equation-of-state), P.R. Roy (plutonium metallurgy), N.S. Venkatesan (terminal ballistics), S.K. Sikka (nuclear design), B.D. Nag Chaudhuri (DRDO coordination), and a cadre of dedicated engineers and technicians. The neutron initiator team led by V.K. Iya and T.S. Murthy, and electronics team led by Pranab Dastidar, collaborated with army engineers to bring the project to fruition.

Indira Gandhi

Politically, it was Indira Gandhi’s determination and sense of India’s place in the world that activated the “bomb option” when the opportunity and necessity converged. Her willingness to authorize the test—despite anticipated risks—demonstrated the centrality of political will in high-stakes technological enterprises.

Government Decision-Making and Approval Process

State secrecy and a “need-to-know” culture permeated the 1974 test, with decision-making limited to the smallest plausible circle. Indira Gandhi’s approval in 1972, concealed behind plausible deniability and the fiction of “peaceful purposes,” allowed technical work to proceed at full steam.

The Atomic Energy Commission operated under the Prime Minister’s Office, bypassing normal Cabinet oversight—a tactic that shielded activities from both foreign and domestic prying eyes but also drew criticism for lack of democratic accountability.

Even within the military, knowledge was compartmentalized: most senior officers and ministers were briefed only hours before the test. This ultra-secret approach enabled India to achieve strategic surprise, underscoring the effectiveness of its internal security measures.

Secrecy and Domestic Reactions

Secrecy was not just a matter of operational prudence but an institutional tradition that dated to the 1948 Atomic Energy Act, which classified most nuclear research as state secret. Parliament and the press were kept at arm’s length, and the “peaceful” label supplied official cover for decades. Critics and public intellectuals—including Praful Bidwai, Dhirendra Sharma, and others—would later argue that the secrecy fostered unaccountable state power and stunted democratic debate about nuclear weapons.

Domestically, however, the Pokhran test was met with overwhelming public approval and pride. Indira Gandhi’s popularity soared, national morale was boosted, and leading scientists became heroes. The operation showed India’s capacity for world-class scientific achievement and was celebrated by the media and political class, with only a few dissenting voices warning of regional arms races and technological embargoes.

International Reactions: Immediate and Enduring

Formation of the Nuclear Suppliers Group (NSG)

The global reaction was swift and, for the most part, negative. The Soviet Union, then a key partner, offered muted support; most other Western nations condemned the test. The strongest official responses came from Canada and the United States, both of whom had supplied the key materials—reactor and heavy water, respectively—that produced the bomb’s plutonium. Canada reacted by ending all nuclear cooperation, citing a violation of supply agreements that stipulated peaceful use. The U.S. suspended fuel supply, tightened export controls, and lobbied for stricter non-proliferation protocols.

Most consequentially, seven nuclear supplier nations formed the Nuclear Suppliers Group (NSG), known initially as the “London Club,” to coordinate export controls on nuclear materials and technology. The NSG’s aim was to prevent “another India,” and it soon became the most influential international body regulating nuclear commerce.

Bilateral and Regional Fallout

- United States: Condemned the test as an “unfortunate step” and advocated for new legislative restrictions (e.g., Nuclear Non-Proliferation Act of 1978). Follow-on sanctions greatly limited India’s technological imports, scientific collaborations, and international financing.

- Canada: Immediate halt to all nuclear and technical support. Existing collaborative reactor projects languished or shifted to full Indian management.

- Pakistan: The sharpest regional consequence was in Pakistan. Prime Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto famously vowed that his country would “eat grass” before falling behind. Pakistan launched its own clandestine nuclear program, turning the subcontinent into a theater of nuclear rivalry that continues to this day.

- IAEA and Global Regimes: The Indian test forced the International Atomic Energy Agency to overhaul its safeguards and inspection protocols. Under international pressure, even Soviet nuclear contracts with India now came with mandatory IAEA safeguards, further frustrating Indian aspirations for technological autonomy.

Post-Test Sanctions and Embargoes

Sanctions implemented after Pokhran-I hit India hardest in nuclear materials, technology transfer, and scientific exchange. The civilian nuclear power program suffered from shortages of heavy water, reactor parts, and engineering know-how. For nearly three decades, these embargoes limited India’s technological growth, particularly in high-end electronics, computing, and dual-use domains (e.g., cryogenics, supercomputing).

Despite these constraints, India pressed forward with its indigenous “three-stage programme,” invested heavily in self-reliant infrastructure, and made technological workarounds, such as the adaptation of thorium fuel cycles and development of home-grown heavy water production.

These embargoes imposed real opportunity costs but did not dissuade India from its strategic objectives.

Impact on the Non-Proliferation Regime

The Pokhran test was arguably the single most important external shock to the global non-proliferation regime after the 1968 NPT took effect. India’s actions exposed core weaknesses in the treaty’s architecture: the ability of “non-nuclear weapon states” with advanced civilian programs to move to weaponization; the lack of universal and non-discriminatory controls; and the “grandfathering in” of five states (U.S., USSR/Russia, UK, France, China) while excluding others.

In response, the NSG required full-scope IAEA safeguards for all future nuclear exports and initiated a new era of export control regimes. The U.S. and other nations tightened laws to require punitive sanctions against proliferation—culminating in the U.S. Nuclear Non-Proliferation Act of 1978, which limited U.S. assistance to countries outside the NPT.

India remained adamant, refusing to join the NPT and insisting on its sovereign right to pursue “peaceful nuclear explosions,” a position that would later be abandoned as the language of minimum deterrence and no first use became the dominant doctrine.

Key Events Leading to Pokhran-I

| Year | Event/Development |

|---|---|

| 1944 | Homi Bhabha proposes creation of Indian physics institute |

| 1945 | Tata Institute of Fundamental Research established |

| 1948 | Atomic Energy Act passed; IAEC created |

| 1954 | Department of Atomic Energy (DAE) established |

| 1956 | APSARA, first Indian reactor, goes critical |

| 1960 | CIRUS reactor operational, makes weapons-grade plutonium |

| 1962 | Sino-Indian War catalyzes nuclear deterrent thinking |

| 1964 | Bhabha publicly advocates “peaceful nuclear explosives” |

| 1966 | Bhabha dies; Indira Gandhi becomes Prime Minister |

| 1969 | Sufficient plutonium for a bomb accumulated at BARC |

| 1972 | Indira Gandhi authorizes bomb project |

| 1974 | May 18: Pokhran-I (“Smiling Buddha”) test conducted |

This timeline underscores the gradual accumulation of technical capability, political will, and strategic necessity that converged in the decision to test.

Pokhran-I Yield in Comparative Context

| Country | Year of First Test | Device Type | Yield (kt) | Test Name |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| United States | 1945 | Plutonium implosion | 20 (Trinity) | Trinity |

| Soviet Union | 1949 | Plutonium implosion | 22 | RDS-1 |

| United Kingdom | 1952 | Uranium gun-type | 25 | Hurricane |

| France | 1960 | Plutonium implosion | 70 | Gerboise Bleue |

| China | 1964 | Uranium implosion | 22 | 596 |

| India | 1974 | Plutonium implosion | ~8 | Smiling Buddha (Pokhran-I) |

Analysis: India’s first bomb was technologically on par with the early post-WWII model—using plutonium and an implosion design, but with a more modest yield reflecting both technical conservatism and a desire for containment.

Conclusion and Enduring Legacy

India’s first nuclear test at Pokhran was a watershed in world history. It demonstrated the ability of a developing country to master, in relative secrecy and despite significant material constraints, the most advanced technology then known. At a stroke, India announced its arrival on the global stage—not only as a scientific power but as a player whose security calculus could shape world affairs.

The test upended the non-proliferation regime, catalyzed tighter controls and sanctions that ultimately spurred further indigenous development, and prompted a subcontinental arms race that endures to this day. It exposed the technological dual-use paradox at the heart of atomic science—a civilian fuel cycle can, given political will, always produce bombs.

In India, the legacy of Pokhran-I persists. It is celebrated as a triumph of national resolve and a validation of the “scientific spirit” first enunciated by Nehru and Bhabha. For the rest of the world, it remains a cautionary tale about technology, sovereignty, and global order.

Today, the Pokhran test stands as a symbol of India’s technological ambition, strategic autonomy, and the complex balance between civilian science and military power.

🔒 Disclaimer

This article is intended for informational and educational purposes only. It presents a historical overview of India’s first nuclear bomb test conducted at Pokhran in 1974, based on publicly available sources and research. The content does not endorse or promote nuclear weapons, proliferation, or any form of military aggression. All views expressed are neutral and aim to provide factual context for academic and journalistic reference. Readers are encouraged to consult official government publications and verified sources for authoritative information. The author and publisher disclaim any liability for interpretations or actions taken based on this content.

Leave a Reply